So many health goals, so little time. I’m probably not alone when I say that the number of healthy behaviors I aspire to is greatly outweighed by the number that I actually motivate myself to do. I know that I should pay attention to portion sizes, exercise half an hour a day, and even take my gummy vites in the morning–and yet I consider it a success if I can knock off two of these on any given day.

Turns out, this is fairly typical. (Perhaps you too can relate?) Much of the time that we fail to be healthy in all the right ways, it’s not because we don’t know how to be healthy. We know what to do, and even want to do it, and yet we still have trouble actually doing it.

It’s not enough to merely want to be healthy. If our intentions translated into actions, then personal decision-making wouldn’t be the leading cause of death in the US (Keeney, 2008). Life would be so simple! We would have no trouble getting enough sleep, managing our stress, exercising and eating well.

Some people have discovered that there’s a way of forcing their intentions into actions. They’ve figured out how to hold themselves accountable, making them dramatically more likely to actually behave in healthy ways. The behavioral science literature calls these people “sophisticated” (O’Donoghue & Rabin, 1999), and they do one thing differently from the rest of us naïfs.

These people impose penalties on themselves for failing to comply with their intentions. They don’t shy away from the opportunity to help their future selves; instead, they welcome the use of commitment devices. Sophisticates realize that they actually need to restrict their own future freedom in order to combat temptation, or laziness, or whatever the barrier is that they face when they ultimately fail to achieve their health goals.

But you don’t have to be sophisticated to set up a commitment device; anyone can do it. Commitment devices can help all us stick to our goals by setting up and enforcing if-then plans. (So, for example, you might decide that if you fail to go to the gym tomorrow morning, then you will not be allowed to hang out with your friends on the weekend.)

At Pattern Health, we allow users to set up commitment devices to keep themselves in check. Users can reward themselves when they succeed, and punish themselves when they fail. One example of this takes advantage of a special feature that we call App Interrupts. People who would like to kickstart their self-control can opt in to use App Interrupts as a contingent punishment.

How do Pattern Health users set up a commitment device? First, they pick a goal that they want to stick to. Then, they attach a penalty that is activated if they fail to achieve that goal. With App Interrupts, this particular penalty involves losing access to the “fun” apps on their phone. If you fail at the task you’ve committed to, you will no longer be able to access the apps on your phone.

So, for example, let’s say your goal is to take your vitamins every morning. If you take your vitamins on Monday, you will keep the normal amount of access to your apps. But let’s say that on Tuesday, you fail to take your vitamins. Now, if you try to open twitter or snapchat (or whatever other apps you decide to include), you’ll be blocked from doing so. Instead of seeing your apps, you see a message like the one in the screenshot.

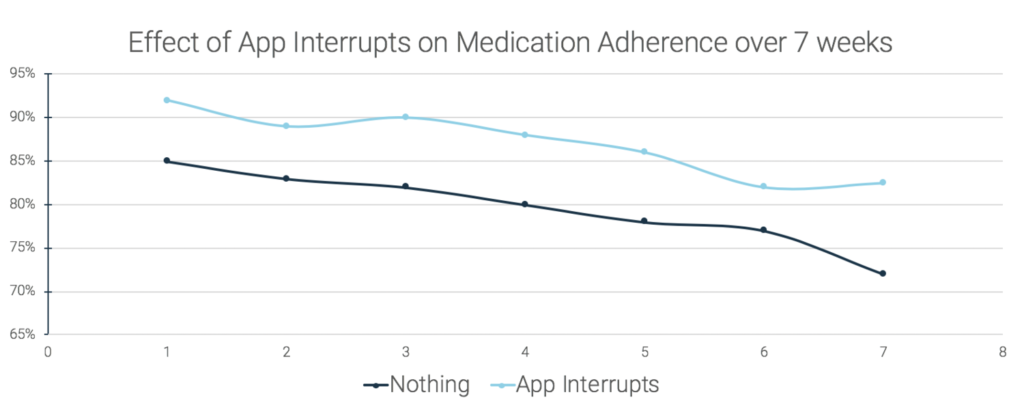

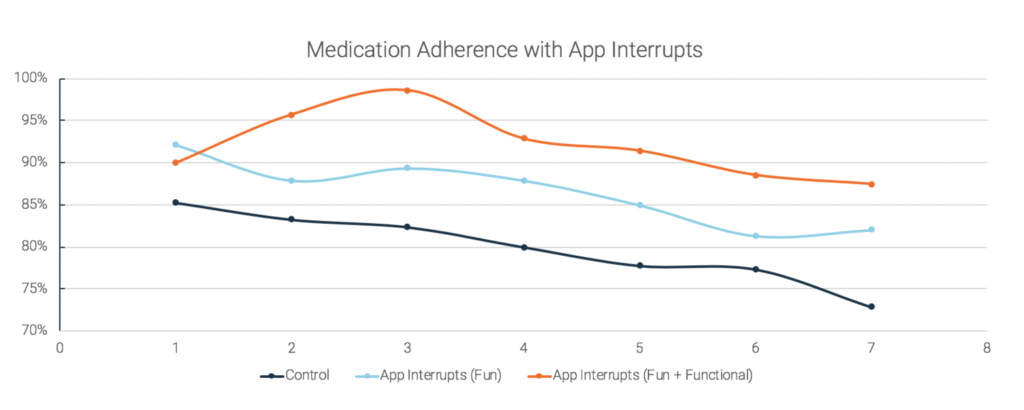

Sound fun? The majority of people who have used App Interrupts as their commitment device felt it to be motivating. And it worked! We found in a pilot study that over a 7-week period, the app interrupts feature led to increased vitamin-taking adherence among participants who were randomly assigned to use it with their commitment device compared to a group of people who did not have access to it.

References

-

Keeney, R. L. (2008). Personal decisions are the leading cause of death. Operations Research, 56(6), 1335-1347.

-

O’Donoghue T, Rabin M. Doing it now or later. Amer. Econom. Rev. 1999;89(1):103–124.

-

Trope, Y., & Fishbach, A. (2000). Counteractive self-control in overcoming temptation. Journal of personality and social psychology, 79(4), 493.