No healthcare buzzword has been more used and abused in the past decade than “patient engagement,” despite the fact that — or perhaps because — there seems to be little agreement on how the phrase is actually defined. The hottest topic at conferences and the focus of countless articles, “engagement” is often hailed as the holy grail of healthcare. According to the prestigious journal Health Affairs, “patient engagement is one strategy to achieve the ‘triple aim’ of improved health outcomes, better patient care, and lower costs” (Health Affairs, 2013).

The focus on engagement is not limited to healthcare. Its popularity as a metric of success prevails in the tech world, reinforced through the design of our systems, from user experience and interface standards to industry funding mechanisms. Dashboards are set up by default to measure clicks, views, likes and shares. Investors look for companies that can recite customer engagement numbers.

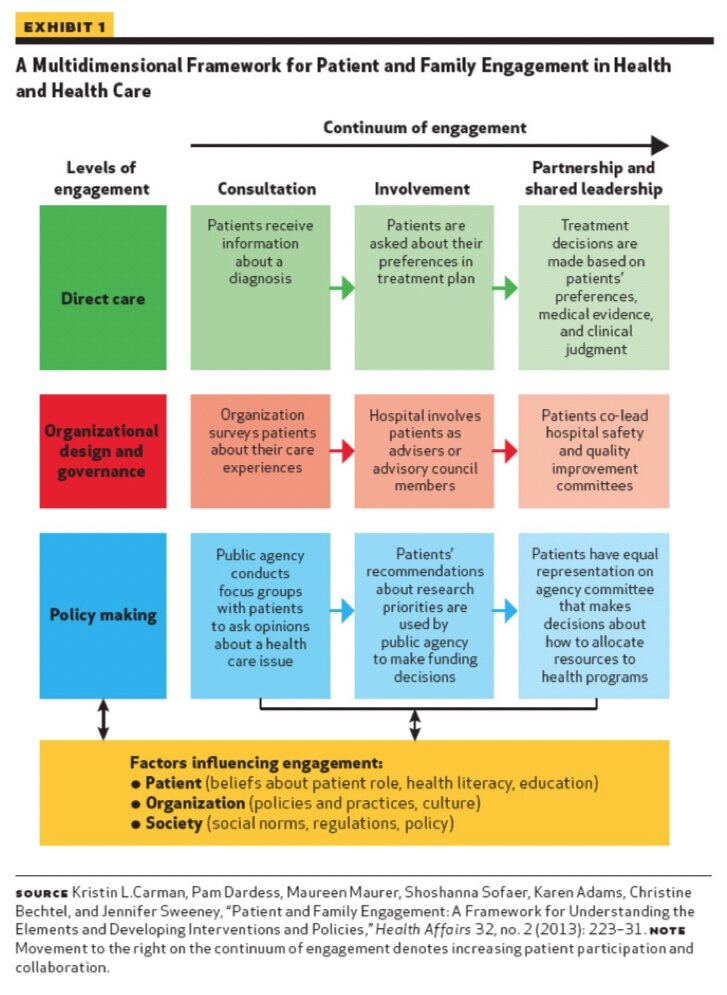

And as a wise person once said, you are what you measure. Organizations that focus on promoting and incentivizing engagement are likely to end with more engaged constituents. This can be a good thing. Engagement is, indeed, an important part of healthcare, and can have implications for not only direct patient care, but also to organizational governance and policy (see Exhibit 1).

However, a too-narrow focus on engagement can detract from other important factors. Engagement on its own does not result in the kinds of outcomes that healthcare organizations hope to achieve. Key behaviors are what ultimately matter and thus what should be measured and incentivized — taking one’s medication, getting enough sleep, drinking water instead of soda, getting an annual flu shot, going for a nightly jog — and engagement is important to the extent that it is effective at facilitating these behaviors.

Connecting Engagement to Behavior Change

In 1985, former Surgeon General C. Everett Koop observed that medications don’t work in patients who don’t take them. And the same is true for engagement in digital health programs. Digital health programs, of course, don’t work for people who don’t use them.

In this way, engagement is necessary for behavior change. But engagement is not the primary objective, nor is it sufficient to change behavior. Imagine a patient, Sasha, who is prescribed a digital health program to help recover from knee surgery. Sasha is excited about the program and enthusiastic about adhering to all of its recommendations. So he downloads an app and goes through all the onboarding steps, accessing all the educational information it has to offer. Sasha proceeds to open and interact with the app every day, fully absorbed in the digital health program. You would consider Sasha a highly engaged patient.

But Sasha is missing something important in his digital health plan. Although he accesses the app’s content regularly, he has not yet tried any of his prescribed physical therapy exercises that will help his leg tissue heal after his knee surgery. Sasha, while highly engaged, has not adhered to the exercises that will help him successfully recover.

Many digital health programs fall short of having an impact because they only focus on getting users to participate in low-impact activities that may boost “engagement” but fail to create the behavior change that leads to important health outcomes. That’s why it’s important to design digital health programs for both engagement and behavior change. In their article on engagement with digital behavior change interventions (Cole-Lewis, Ezeanochie & Turgiss, 2019), researchers propose a framework in which engagement can promote behavior change: when a user both has the appropriate level of interaction with a digital health tool and the program is designed to target the specific behaviors needed for improved health outcomes.

Designing for Behavior Change and Real Impact

Once you have established the key behavior that will lead to your desired outcomes, you can decrease friction (eliminating the things that get in the way of performing that health behavior) and increase fuel (adding elements that make the behavior more likely). There are many ways to decrease friction and increase fuel, and some concepts will be better suited to a given situation than others. For example, you could have your users set an implementation intention to remember to get their flu shot after picking the kids up from school this Wednesday. Or they could invite their friends to a care circle to provide social support and accountability to their exercise goals. By tapping into the behavioral science literature to design for behavior change, you can ensure that your users will be both engaged and behaving in line with their long-term interests.

References

-

Patient Engagement (2013). Health Affairs Health Policy Brief.

-

Cole-Lewis H, Ezeanochie N, Turgiss J. (2019). Understanding Health Behavior Technology Engagement: Pathway to Measuring Digital Behavior Change Interventions, JMIR Formative Research 3(4):e14052