“That was an incredibly scary time, being as young as I was, thinking about possibly dying, leaving my young children,” reflects Kirsten of her initial experience with heart failure. Kirsten is a patient advisor in CONNECT-HF, an ongoing study to better understand how to help patients when they leave the hospital just after being diagnosed with heart failure. The CONNECT-HF study, powered by Pattern Health and led by researchers at the Duke Clinical Research Institute and the Center for Advanced Hindsight, is a nationwide clinical trial being conducted with 8,000 participants at 161 hospitals across the United States, and is funded by an independent investigator grant to Duke University from Novartis.

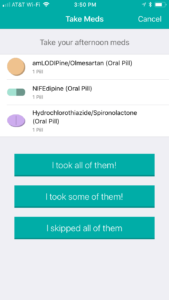

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the US. One in 5 Americans have heart failure, specifically, a chronic condition that is rising in incidence. And it’s a condition that often goes unmanaged. For one thing, patients struggle with the incredible degree of complexity that comes along with heart failure. Take the fact that the typical heart failure patient is prescribed 8 different medications, on average — each with their own side effects and interactions. The same patient is often asked to lose weight, decrease stress, monitor their fluid intake, avoid or limit alcohol and caffeine, adjust their diet, become physically active, track their blood pressure, and more.

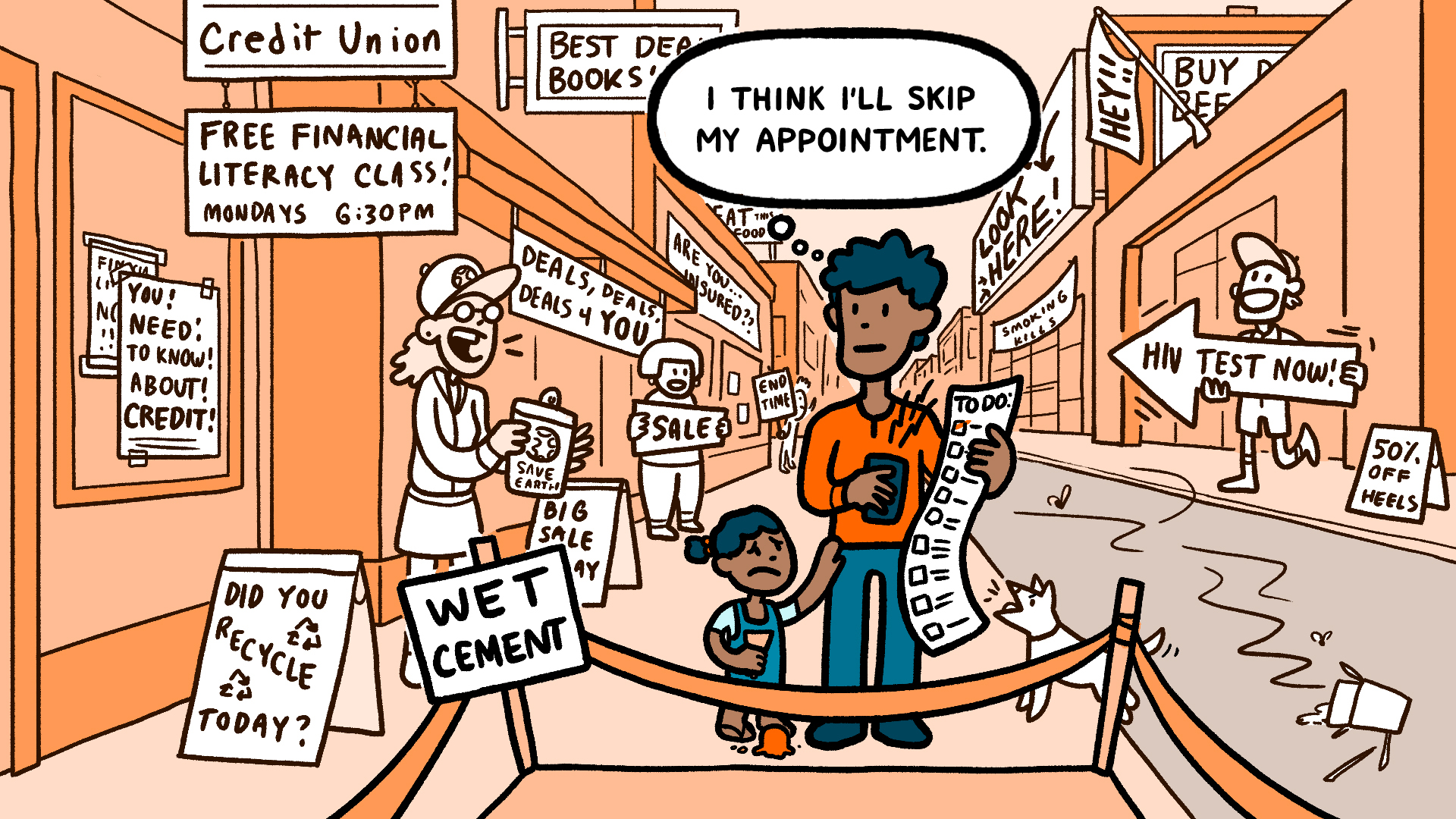

Patients are asked to remember an impossible amount of information, act on that information in certain cases (but not in others), and consistently change their habitual behaviors — all on top of their usual life demands. They have to not only know what to do, but also find the time, means, and motivation to do it. And patients don’t act in a vacuum. The way we tend to imagine patients making health decisions is quite different from how they actually make health decisions — surrounded by conflicts and pressures, situational demands and internal stressors.

“At the time I was diagnosed [with heart failure], I didn’t have the tools at my disposal. You’re very scared, you’re very worried about what’s gonna happen,” says Jose, another patient adviser in the CONNECT-HF study powered by Pattern Health.

Patients with heart failure, like Kirsten and Jose, feel motivated to stick to their care plan to prevent rehospitalization and improve their quality of life. However, despite their hopes of achieving these important outcomes — for patient X to attend her granddaughter’s college graduation, or for patient Y to get up the stairs without assistance – patients’ good intentions to stick to their care plans don’t always align with their actual behavior.

It’s a lot to worry about. And patients do worry.

Actual behavior is more complicated than the transposition of hopes and dreams into reality, and can be highly influenced by two basic forces: friction and fuel. Frictions get in the way of behavior change, and fuel promotes it. As the first of the three laws of human behavior declares, “Behavior tends to follow the status quo unless it is acted upon by a decrease in friction or increase in fuel.” This means that if a patient is not in the habit of exercising, she will likely continue to be sedentary unless physical activity becomes easier to initiate (a decrease in friction) or more attractive to do (an increase in fuel).

We can promote positive health behaviors in patients with heart failure by decreasing friction and adding fuel

If our ultimate goal is to understand the behavior of heart failure patients in order to engage them in their care and promote better long-term outcomes, we can first outline the types of friction that get in the way of positive health behaviors, and the types of fuel that can encourage patients to adhere to their care plans and successfully manage their condition.

One behavior that is critical for heart failure patients is stepping on the scale. Small changes in weight over short periods of time are often due to fluid retention that may be symptomatic of a larger problem with a patient’s heart, and the detection of abnormal weight fluctuations can be used to prevent rehospitalization in this at-risk population through a supervised adjustment in medication dosage. Because heart failure patients who reliably monitor their weight are likely to detect such fluctuations, patients are generally advised to track their weight over time and note any extraordinary changes (the standard rule of thumb is to reach out to one’s doctor after gaining > 3 pounds in a day or > 5 pounds in a week).

And yet, despite the critical importance of weight tracking, many heart failure patients don’t reliably step on the scale. Even when heart failure patients intend to monitor their weight, there may be too many barriers or too little incentive to do so. In collaboration with the Duke Clinical Research Institute and the Center for Advanced Hindsight at Duke University, we sought to decrease friction and add fuel in order to encourage heart failure patients to track their weight more consistently.

Decrease friction to help heart failure patients

We can identify the friction that gets in the way of weight tracking, and then decrease that friction in order to help patients track their weight. What are some important frictions that might deter a heart failure patient from tracking their weight?

To start, the burden of simply tracking any behavior can be so high that it won’t get done. When it’s annoying to track a behavior — even just slightly annoying — people are less likely to do it, even when the potential long-term benefits of tracking are high (such as avoiding rehospitalization). When tracking a behavior is a burden, it helps to relieve that friction by making the tracking activity passive or automatic. A patient’s measurements can be automatically recorded when they step on the scale each morning rather than requiring the patient to keep track of them. Or weight measurements can be taken without a patient even having to remember to step on the scale (in a soft mat placed by the bed so that patients step on it every morning when getting up, or a bed that doubles as a scale and takes a measurement each night). Any way that we can decrease friction by relieving patients of the tracking burden is an improvement.

In cases where tracking can’t be done automatically (as in a rating of subjective mood or tracking medication when the patient doesn’t have a passive option), we can make the experience as easy as possible so that patients can quickly enter a measurement without much effort.

Add fuel to help heart failure patients

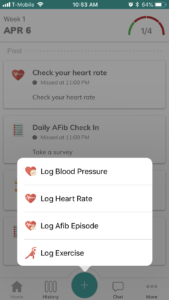

We’ve decreased friction by making it simple to track behavior, but what more can we do? What opportunities are there to add fuel? Recall, fuel is anything that increases the likelihood that patients engage in behaviors. One type of fuel is the good old-fashioned reminder (see screenshots below). It’s almost too obvious to say: to monitor weight with a standard scale (not the futuristic type that lives inside our beds), patients have to remember to step on the scale. And when habits are not yet established, well-timed reminders can be an effective form of fuel for overcoming this friction.

By updating the old-fashioned reminder to align with patients’ routines, reminders can become infinitely more helpful. (Sending a notification after someone has gone to bed, for example, will not serve as a very effective reminder!)

In a study of a group of heart failure patients, we compared three different versions of reminders to a control group that received no reminders. We tested a reminder sent in the morning with a list of tasks for the day (called the “morning summary”) against reminders sent just before a task should be completed (which we called “real-time” reminders), in addition to a final group that received both the morning summary and real-time reminders. We found that the group that received both types of reminders (the “morning summary” and “real-time” reminders) was more engaged than the group receiving either type of reminder on its own, and much better than no notifications at all. And while engagement is not enough for behavior change, it is certainly one important component.

Reminders are essential when forgetting is the problem, but they rarely go the final mile to full-blown behavior change — particularly when memory is not the only problem. In this case, pairing reminders with a more motivating form of fuel can make them more effective. One such form of fuel that readily complements reminders is the power of social support.

There is a great deal of evidence in favor of social support: when patients feel supported by their friends and family, they experience better health outcomes. Pattern Health’s care circle brings patients’ social connections to the forefront, empowering patients to leverage their existing networks for accountability and social rewards. Patients choose who to invite to their care circle, and that group gets notified of the patient’s activity (see screenshot below). By involving the patient’s chosen group in their care, it creates opportunities for supportive conversations and can lead to better outcomes in the long term.

These forms of fuel — reminders and support from others — are only two types out of many. (The friction and fuel framework outlines the full spectrum of forces, including incentives, appeal, and visceral factors.) And while the examples covered in this white paper only scrape the surface of friction and fuel, they do illustrate how the framework can be used in practice to help patients reach their health goals, making a real impact on both behavior and outcomes.

Being a patient is not easy. But we can help them succeed by decreasing friction and adding fuel to make their desired behaviors easier and more appealing to do. By keeping behavioral science in mind when designing digital health programs, we can architect systems that effectively promote lasting behavior change and provide patients with the support they need. So when heart failure patients like Kirsten or Jose are discharged from the hospital, they can be better equipped to manage their condition from the start.

Download the full PDF white paper:

"*" indicates required fields