Originally published in Forbes by Aline Holzwarth

For the 90% of Americans now ordered to stay home (up from 20% just a week ago) to stave off the risk of catching and spreading the novel coronavirus, keeping a strict distance from others is beginning to feel like the new normal. Every other conversation is peppered with observations from friends, family and coworkers on how much has changed in such little time, and how easily we have found ourselves slipping into new patterns. As physical distancing norms shift at light speed, we are surprised to find ourselves outraged at the sight of a grocery store worker without gloves, or overcome with a strangely visceral reaction upon seeing a group of people standing fewer than six feet from each other, when just a few short weeks ago these were completely normal scenes.

But how did we go from living our daily lives as creatures accustomed to being in groups to having a physiological response to a beach full of people: heart racing, nostrils flaring?

Large scale changes in physical distancing are due to shifting social norms

These landslide changes in behavior are not due to enforcement or policing (which have been minimal in the US); rather, they are due to shifting social norms that have accompanied the closure of businesses and sheltering recommendations. They are a direct result of social proof and peer pressure. Indeed, social norms can have a strong influence on behavior — not only as a response to what others do, but also what others find desirable. Humans take cues from others to understand what is socially acceptable, and adapt their behavior to ensure that they fit in. Behavior can be contagious, as researcher Jamil Zaki has shown with the spread of generosity and kindness. And in unfamiliar situations, or in times of uncertainty, people are particularly attune to behavioral cues from others. The outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic is a clear case of unfamiliarity and uncertainty, and it’s no surprise that new social norms around physical distancing are swiftly taking hold.

There are two primary ways that social norms around distancing have been communicated: the approval of positive prevailing behaviors (“I’m staying home. You should, too”) and the disapproval of negative but increasingly uncommon behaviors (“Look at those jerks at the beach who haven’t gotten the memo”).

Approval of positive behavior reinforces new norms

The first type of messaging, establishing the positive social norm of sheltering in place, is seen in the media in cases like the photographic piece in the New York Times “The Great Empty,” which features normally-crowded spots all over the world that have been all but abandoned. The photos are hauntingly beautiful, and they vividly send the message that everyone is staying in.

On top of this are countless examples from social media, where influencers of all brands encourage their followers to stay home. It is in this way that social media can be used for good: as sociologist and physician Nicholas Christakis and political scientist James Fowler demonstrate in their book “Connected: The Surprising Power of Our Social Networks and How They Shape Our Lives,” social networks can spread ideas and can impact behavior change through the social norm messages that they embody.

Importantly, different sources of messaging can appeal to people differently, notes behavioral scientist Eugen Dimant. The audience that will respond most to Arnold Schwarzenegger’s urging is different from the audience tuning into the Centers for Disease Control. And these audiences are different from the 210 million fans locked to Cristiano Ronaldo’s instagram or the two million people who ‘liked’ Taylor Swift’s photo of her cat in quarantine. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to persuasion. But in this rare time in history, there are converging examples of a wide range of influencers all echoing the same sentiment (Stay Home) in different ways. This diversity of voices has amplified the megaphone of expert epidemiologists and healthcare workers, spawning a far greater impact than any one voice could achieve.

Disapproval of negative behavior reinforces new norms

The second type of social norm communication is the disapproval of those who violate the new norms. In what has been called “quarantine shaming,” the minority of people who transgress and have not yet adopted physical distancing behaviors are targets for outrage, treated like defectors in a public goods game. Social accountability and productive shame can be an effective means to behavior change, as people generally try to behave in ways that will be accepted by their peers. In the case of the novel coronavirus, the majority (physical distancers) are sending a clear message to the minority (non-distancers) that their behavior is unacceptable to society at large.

Both the social approval of positive behaviors and disapproval of negative behaviors can work together to promote new norms, and cause such norms to spread like the virus they are combatting. But unlike the coronavirus, the contagious nature of norms around physical distancing can have life-saving consequences — results that we may not be too far from achieving. Research from Damon Centola shows that the tipping point for the spread of social norms can be as low as just 25% adoption to reshape society.

The tipping point has been crossed

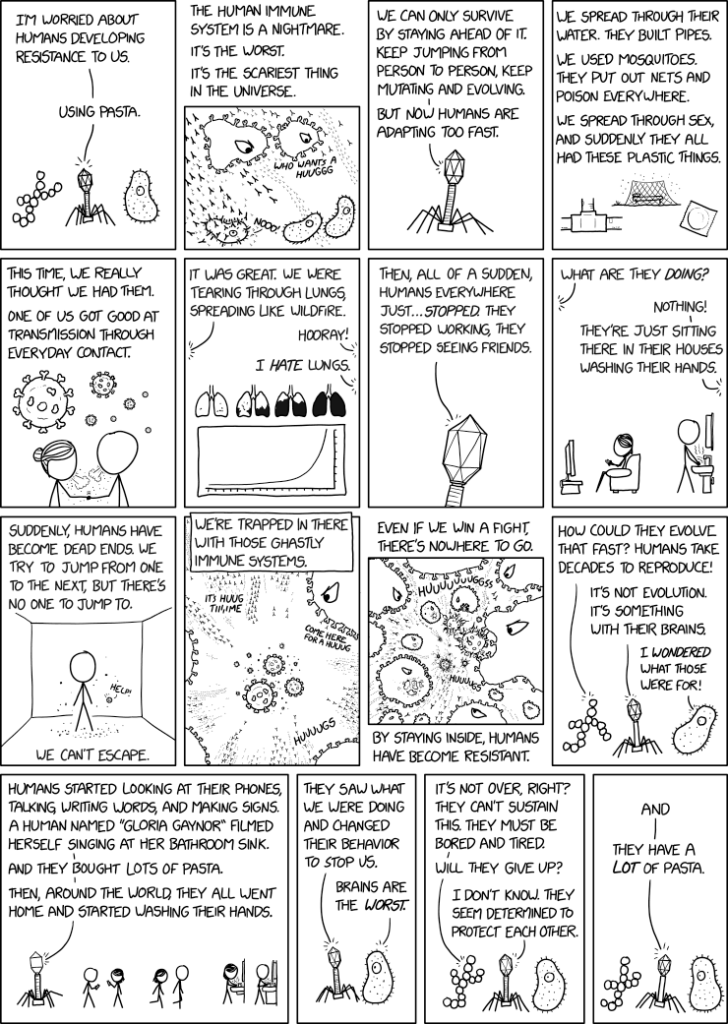

Indeed, it appears that we have already surpassed the tipping point for the behavior change necessary to flatten the curve and buy time for health systems to prepare for the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic yet to come. Evidence from digital tracking of fever across the US gives hope that the rate of infection is beginning to slow as a result of physical distancing and sheltering behaviors. We’ve used the strategies of a virus to fight the novel coronavirus; the social norms established through the approval of positive behaviors and disapproval of negative behaviors are successfully preventing the virus from spreading. And if the notorious XKCD is correct, the coronavirus is shaking in its boots.